The post Deja Vu: China’s Relations with the West appeared first on China Research Center.

]]>Based on my experiences in China over the years, I saw a growing shift toward practicality, but today we see another reversal — to the reestablishment of 体 as primary. Along with that reversal, foreigners’ role in China’s development is also changing.

Living in Nanjing in the Early 1980s

In 1982, I was one of the early international students to go to China to do research. Graduate students from several countries had already been allowed to study there, and the U.S. followed a few years after normalizing relations in 1979. I was the second or third cohort from the U.S. to be sponsored by the Committee on Scholarly Communications with the PRC.2 My project was to analyze Jiangsu Province as a case study of the effect of central policies on local development. Since reforms were so new, I first researched the Mao decades and later extended my analysis to the reform period.

Data was essential to my project, but it was also problematic. The government classified economic data as a state secret. Some scholars had been detained for having data. A conundrum, indeed. At least I had the U.S. government behind me in this endeavor. My strategy was to create tables with the headings of the information I wanted to collect and have the respective offices fill in the blanks. In hindsight, it was perhaps wishful thinking that this approach would succeed. As it turns out, there was a major effort across China, at all levels of administration, to put together data yearbooks. Because of this, officials did, in fact, fill in (at least some) of my data tables.

Since my focus was Jiangsu Province, I applied to do my research at Nanjing University (Nanda) in Nanjing, the provincial capital. I lived in the university’s foreign compound with about 150 other students and faculty from around the world, some of whom had Chinese roommates. We had heat and hot water several hours a day, and food that was substantially better than the regular university canteens, but life was quite harsh relative to what we were used to.

The Economics Department was technically my host, but they did not invite me to meet with them or any students studying economics at any time throughout the two years I was there. However, I could audit courses, which I did. In the last semester of my stay, I finally met one of the professors. Professor Zhu was responsible for helping me make contact with the officials I wanted to interview in Nanjing and several other cities in the province. Professor Zhu spoke English, as he had worked in international trade, while most other professors did not. I was learning Chinese but needed help with translation during the interview process.

In 1982, western foreigners studying or doing business in China was a new development, allowed to support the leadership’s economic reform efforts. We were treated hospitably and with respect. But there was an underlying tension, perhaps suspicion, that foreigners could contribute to China’s reforms and development, but may also be dangerous. The university administrators were responsible for our well-being and so were careful to keep a close eye on us. Anyone who wanted to visit us had to register and show ID. Our mail was read. Our boxes were opened. If we wanted to travel outside the city limits, we needed to apply to the university and the local police station for permission. Just riding our bikes within Nanjing, we would find signs at the boundaries of the city that said foreigners could not go further.

Daily life was challenging, and our environment was restricted and monitored, but we felt there was a good chance that society would move toward more openness. Unfortunately, the opposite is true today. While daily life in China is quite comfortable for most by now, the signs are that the society is closing again. For example, the universities are under pressure to use textbooks by Chinese scholars, and not those written by foreigners. Authorities monitor classrooms with video cameras, and professors can quickly get into trouble for saying something that questions or counters the Party’s line.

Change and Backlash3

Two incidents occurred while I was in Nanjing that reflected the tensions and disagreements about the changes afoot in those early days: first, the “Spiritual Pollution” campaign and second, a demonstration at Nanda. People desired change, but not surprisingly, they also wanted to choose the reforms that benefited them the most. And China’s age-old dance between importing foreign ideas (用) and finding a Chinese solution (体) was also at work.

The Spiritual Pollution Campaign

The Spiritual Pollution campaign in the early 1980s was a backlash against the dangers of China opening too fast and of adopting ideas that went against the strategy of maintaining stability by the political elites. Today, the pressures on professors, students, and citizens to conform to the leadership’s view of China’s path is reminiscent of these early years. The difference is a new looking back rather than looking forward.

The Spiritual Pollution campaign’s main message was that socialism could not be criticized. Intellectuals were discussing the existence of alienation under a socialist system. Markets may be possible under socialism, but alienation is not. Thus “dangerous” ideas, such as those of Sartre, were to be criticized if discussed at all. People who had written pieces favorable to Sartre, or discussed alienation, were asked to write their ideas anew. Specifically, at Nanda, one professor was criticized for an article he had written on Hu Shih, a well-known Chinese academic who had studied and promoted pragmatism.4

While targeted primarily at harmful ideas in intellectual circles, the campaign also touched on areas of laxity and unethical behavior. For example, Party spokespeople and written editorials criticized books and magazines for printing stories about love affairs and other situations deemed “indecent.” Also suspect was long hair, facial hair, and revealing attire. One rumor was that all city workers in Beijing were subject to hair and dress regulations.

It was understood, of course, that a main source of these bad influences was foreigners and their decadent societies. Reforms had meant China had much more contact with the international community, and some of this contact was deemed harmful. Being a foreigner in China, then, raised interesting contradictions. Our dress and culture were indecent (even if desired), but our technology and markets were necessary to modernize China. Ironically, this situation is back in spades in China today.

The most immediate problem for us at that moment was judging whether this campaign was severe enough to cause trouble for the Chinese with whom we associated. Our experience was that the Chinese were not worried—aside from the few targeted intellectuals—and that the campaign did not involve us in their minds. People said that indecency was not desirable in books, magazines, and films, but nonetheless, everyone was informed of the details of the latest “indecent” story. But Chinese friends did not stop seeing us, and on the surface, at least, only the amount of gossip changed.

At the university, however, there were required meetings for students, faculty, and administrators to discuss the message of the campaign. These meetings were reminiscent of the numerous campaigns before. In October 1983, the Foreign Affairs Office asked us if we would like to discuss “spiritual pollution.” We agreed, thinking we could ask what this meant for us and if the restrictions on our contact with Chinese people would increase. Instead, the meeting consisted of a two-hour speech on the question of alienation delivered by a university official in perfect line with recent People’s Daily editorials. By December, after going through the motions, we all — Chinese and foreigners – had forgotten that “pollution” had been a problem.

The Nanda Incident

Another reaction to China’s reforms occurred during three days in May 1984. This event began on campus but eventually involved the provincial government, a central investigation, and the international news media. The catalyst for this incident was the status of Nanjing University, but the key issues were the students’ right to demonstrate and factionalism on campus. Earlier in May, the Ministry of Education chose 10 institutions to receive more autonomy and an extra 100 million yuan each to help them quickly implement their educational reform and improve programs. To the dismay of the university community, Nanda was not among this privileged group.5

On May 28, posters appeared on campus criticizing the university leadership for lack of concern for intellectuals and the overall quality of the university. The former university president, Guang Yaming, had been transferred and not replaced, leaving Zhang De, the Party Secretary, in charge. The Party Committee was powerful within Nanda’s administration, and removing Guang gave the dominant party group free rein. One of the confrontations between Guang and the Party Committee had been over the status of intellectuals. To improve the situation of professors in line with current reform policy and compensate them for poor treatment during the Cultural Revolution, Guang wanted to add their years spent in school to their work time to increase the years counted in seniority. Since seniority determined access to housing and other perks, this change would mean professors would benefit at the expense of other university employees. This change was not in the interests of the Party Committee, and they succeeded in getting Guang transferred.

After Guang left, three separate elections failed to fill the position. The students accused Zhang of being instrumental in preventing the election of a permanent, reform-oriented president, and they demanded the return of Guang. According to one account in the Hong Kong paper, Pai Hsing, the Party Committee tried to appease the students by agreeing to meet with them to discuss their proposals, but the students rejected this.6 The paper also implied that the students decided overtly to demonstrate their displeasure when the Party Committee asked the Nanjing Armed Police to patrol the campus.

From the beginning, in addition to the university’s status, a key issue was the rights of students to disagree with, and try to influence, the university administration. This aspect of the conflict was reminiscent of the Cultural Revolution, i.e., when the bureaucracy blocks established methods of change, then challenged the bureaucracy. The students drew on China’s Constitution to support their right to demonstrate. The university also drew on the Constitution to argue that the demands for reform were correct but that the students’ method of dissent was disruptive and illegal. The students were to meet formally with university officials and not write posters or demonstrate. This position was repeatedly read over the loudspeaker in the evenings when people would gather. Besides this action, however, the university did nothing directly to stop the activities. The students ignored the instructions and put up many large and small-character posters. The lights on the outdoor bulletin board were left on all night so people could read and discuss them.

By the second day, the criticisms in the posters had moved from generalizations about poor leadership to criticizing Zhang by name, pointing to the influences of “leftism.” The activity and excitement on campus then built quickly. Students wrote more posters and discussed the issues late into the night, and people crowded the streets in the evenings. During these events, international students mingled freely among the crowds.

On the third day, a rumor spread that there was to be a demonstration involving a march from campus to the provincial government buildings about two miles away. The students felt they had met a dead end in dealing with the university and decided to take their complaints to provincial leaders. That evening the number of people on the campus streets swelled to make quite an event. Peddlers were selling spiced eggs and ice cream; people brought their children; and the loudspeaker was repeating its message, apparently to non-listening ears.

Eventually, we heard that people had gathered just outside the gate and began to walk, picking up people as they went. I and a few others rode our bicycles to catch them, but not knowing their route, we went straight to the provincial government buildings and waited. The atmosphere was tense, but no one said anything to us. Minutes later, the marchers arrived. The group was orderly and quiet but was large by then, with well over a thousand people. For a few moments, it seemed there would be a confrontation. Public security was blocking the major intersection, but the group did not slow its pace. Then, just before the group reached the blockade, the police moved aside.

For the next hour, little happened. I was standing in the back on a cement wall overlooking the square. The gates to the government complex opened and closed several times. I heard later that the provincial officials asked the students to send representatives inside, but people were reluctant to volunteer. Eventually, several people volunteered to negotiate, and a meeting between the students and the government was set for the next day. After some time, the crowd thinned out and the demonstration ended.

We never knew whether that meeting took place or not. However, the next day the university abruptly ended all activities relating to dissent on campus. The bulletin boards were now kept unlighted, posters were forbidden, security checked IDs at the university gate, and university officials questioned the student leaders. The incident was over.

Two other things of importance related to the Nanda incident happened. First, during the first two days of activity on campus, the situation was reported by Voice of America; and second, Beijing sent an investigation committee shortly after the demonstration, which further curtailed discussion and increased rule enforcement on campus. Perhaps if the international press had not reported news of the event, Beijing would not have become so directly involved in provincial and university affairs.

On the one hand, foreigners’ knowledge of what is going on may increase the impact of a protest by adding pressure to resolve the issues. On the other hand, officials may fear how foreigners will interpret and report the incident and, therefore, may react by quickly ending the dissent and punishing the Chinese people involved. Another aspect of the position of foreigners in China is that we are all under suspicion of being spies. During this incident, a rumor that Voice of America had reported it during the first two days did not allay these suspicions. Even the foreign community was surprised at how quickly this incident became known beyond the university. As this experience suggests, our presence alone may cause problems of which we are unaware.

We had no way of knowing at the time that student protests would put such monumental pressure on the Communist Party and Chinese government. Early protests like this were precursors to events that led to the violent Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989. Such protests are difficult to imagine in Xi Jinping’s China today.

A New Day

Over the period I lived in Nanjing, the restrictions eased slowly, and people were more relaxed about talking with us. More cities were opened to foreign investors and travel, although only certain hotels could host foreign visitors. Over time, China continued to relax restrictions across society. In contrast to the lack of contact with peers at Nanda in the early 1980s, I developed deep friendships over the years and fruitful academic exchanges and collaboration. I traveled alone, with my husband, with friends, and with student groups, visiting every province and region in China. We were free to explore and learn by talking with whom we wanted.

Now, under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, China’s trend toward opening is reversing – abandoning 用 for a new type of 体. Covid-19 is the most apparent reason for restricting society, but it also provides a convenient excuse. Behind the currently closed borders is a growing narrative that China no longer needs foreign ideas, skills, or capital. Western values are critiqued and rejected, replaced by a mix of Confucian and modern Chinese thought. The term “spiritual pollution” has returned to conversation. The leadership harshly critiques any expression of alienation, such as the “lying flat” trend of young people who talk about doing as little as possible to get by since success, as customarily defined, is so elusive.7 Even English is being downplayed after a spectacularly successful push to teach it across the Chinese education system. Moreover, authorities expect Chinese academics to conduct research in support of China’s policies and do it with decreasing collaboration with western scholars.

While economic development continues apace, the range of allowed debate is narrowing, along with individual freedoms as the CCP returns to its Marxist, socialist roots. President Xi talks of pushing China into the next stage of socialism with “common prosperity.” In the past, we heard Chinese people sometimes say the CCP stood for the Chinese Community Party – a reference to a gentler party leading social progress. Today, the Party is returning to sticks over carrots and is increasingly feared. One can only guess that President Xi sees taking the socialist mantel as his way of maintaining his and the CCP’s power for years to come.

The post Deja Vu: China’s Relations with the West appeared first on China Research Center.

]]>The post Is the World Ready for China Risen? appeared first on China Research Center.

]]>Given this likelihood, I ask whether rich democracies, in particular the United States, adequately prepared for a Chinese superpower – especially as its likelihood increased along with China’s economic and technological development. I take a neutral stance as to whether China’s rise should be seen as an opportunity for a more peaceful and prosperous global future or a threat to the global status quo, the Washington consensus, liberal democracy, or the United States in particular, or somewhere in between. I take this neutral stance because a lack of preparation for China’s rise should be concerning for Panda Huggers and Dragon Slayers alike. Dragon Slayers, hawks who want to work to contain, challenge, or even fight China, could find that the U.S. has not done enough to prepare for a – hopefully – preventable conflict with China, or to check its growing influence. Panda Huggers, doves who would prefer to engage China, might conclude that we have failed to develop expertise and put far too little emphasis on peaceful efforts to cooperate as well as compete economically with China.

There is no checklist to prepare for a rising superpower. Yet, this article will provide a survey of some of the efforts, made and unmade, to prepare for a China-dominant world. Specifically, it will consider military, economic, and educational readiness for a China Century.

Military

China’s rise and the modernization and professionalization of its military have proceeded apace since national defense was included as one of Deng Xiaoping’s Four Modernizations in 1977. While the U.S. military was considering its role as a world policeman in the 1990s and a counterinsurgency force in the 2000s, China was focused on projecting power where it mattered to the PRC, near its borders and surrounding seas, particularly toward Taiwan. In 1996 when the United States and China almost clashed over Taiwan, General John Shalikashvili, then chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, dismissed the PRC’s ability to invade Taiwan, concluding that “China simply lacked the sealift resources, especially amphibious ships.”1 China’s threat was dismissed as the “million man swim,” a term that is now frequently cited in articles explaining how much the realities of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan have changed since the 1990s.

The U.S. military’s focus, tactics, and doctrine in the decade after the 9/11 attacks were fundamentally mismatched to containing, dissuading, or confronting China. As China forged ahead with its aircraft carrier program, the U.S. Navy contemplated reducing its aircraft carrier groups. Military experts concerned with China argue for the need for weapons and strategies that can block China’s anti-access/area-denial capabilities (A2/AD). Since 2009, the Pentagon has been pushing just such priorities in the form of the Joint Concept for Access and Maneuver in the Global Commons. Yet, according to Michael Beckley, “[T]he U.S. defense establishment has been slow to adopt this [China] strategy and instead wastes resources on obsolete forces and nonvital missions.”2 While the U.S. has not created a unified strategic vision for how to prepare for China’s rise, it’s not for lack of trying. There have been several proposed Joint Concepts, Strategic Concepts, Expeditionary Warfighting Concepts, and other schemes. Implementation of such grand strategies is expensive, difficult, and time-consuming, and shifts in politics have complicated it further, as have wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Whether its preparation for dealing specifically with China has been as effective or efficient as it could be, the U.S. military enjoys such substantial advantages that it is hard to conclude that this is an area where rich democracies have failed to prepare. Three factors stand out. First, the United States spends almost four times as much on its military as China. Second, aside from Russia, every other major military spender is a close U.S. ally. Third, the Chinese military’s lack of war-fighting experience contrasts sharply with that of the United States, which has, for better or worse, been involved in numerous conventional and unconventional conflicts in recent decades. While we hope the question of whether the U.S. and its allies can handle China militarily will never need to be answered, it seems clear that it is the field in which preparations for China’s rise have been least insufficient.

Economics

For those, like this author, who believe it best not to consider China primarily as a military threat and that prophecies about coming conflicts are self-fulfilling, a lack of preparation and investment in non-military areas is more distressing. Headline figures on balance of trade have their place, but do not reflect complex realities such as the U.S. earning a much greater share of the profits than China for every iPhone assembled in the PRC. Direct efforts to “get tough on China” on trade have proved dismal failures; from Obama’s early attempts to Trump’s more recent ones, they have generally hurt the U.S. more than China. Far more problematic than today’s headlines about trade imbalances, therefore, is a reluctance to invest in the research, infrastructure, and education that would help make rich democracies economically competitive with a rising China in the coming decades.

Much of China’s economic success was the result of scrappy small and medium enterprises organized in industrial clusters. Foreign companies and consumers were some of the biggest beneficiaries of that economic success. Yet, the Chinese state has also invested heavily in making China internationally competitive. From 2000 to 2017, Chinese R&D spending increased 17 percent a year compared to 4.3 percent in the U.S. China eclipsed U.S. science spending in 2019.3 The Chinese state also invests in, supports, and protects Chinese companies. As the Wall Street Journal’s Chuin-Wei Yap wrote, “Huawei had access to as much as $75 billion in state support as it grew from a little-known vendor of phone switches to the world’s largest telecom-equipment company.”4 Rich democracies could have maintained an economically productive relationship with China while still preparing for its rise by spending on R&D. Yet until recently, they did not even attempt to keep up. As late as 2020, the U.S. Senate introduced a bill that offered a mere $1 billion for the development of 5G alternatives to Huawei.5

The United States also failed to invest in other areas that could help keep it competitive with China, especially in infrastructure and education. China opened approximately 24,000 miles of high-speed rail between 2008 and 2021 and now accounts for around two-thirds of the world’s total high-speed rail. Europe has less than 6,000 miles and the United States only 34. While U.S. bridges have begun collapsing, China has built around a quarter-of-a-million new bridges since 2010.6 China went from graduating half as many STEM (Science, Technology Engineering, and Math) Ph.Ds. as the United States in 2000 to 50 percent more in 2019.7 Taken together, it seems that China has surpassed the rich democratic world in almost every aspect of investment, that this trend was clear for decades, and that little was done to address it.

There are signs that the momentum is beginning to shift in the space of only a year or two. In December of 2021, the European Union announced its €300 billion Global Gateway scheme (designed to compete with the Belt and Road Initiative). In February of 2022, a dozen former U.S. national security officials from both parties called for the U.S. to pass the $250 billion dollar China competitiveness bill.8 It might appear that rich democracies may have finally woken up to the scale of resources necessary to keep up with China economically both at home and abroad, but there is still reason to be skeptical. The Global Gateway scheme was in part a repackaging of existing investment and aid, and neither the China competitiveness bill nor Biden’s $1 trillion infrastructure bill have yet to pass. Time will tell if these efforts succeed, but for now it appears that the momentum has at last begun to shift and that rich democracies are starting to assess the potential influence of China realistically, if a decade or two late.

Education

Nowhere is the gap between China and rich democracies as evident as in the sphere of education. In 2012, one of the founders of Blackstone private equity group set up the Schwarzman Scholars program to send top U.S. students to study at Beijing’s Tsinghua University, explaining that “China is no longer an elective course, it’s core curriculum.” Yet in most rich democracies, China is not even in the course catalogue. From kindergarten to graduate school, Europe and North America are failing to prepare their students to work and prosper in a century that will be Asia- and China-centric.

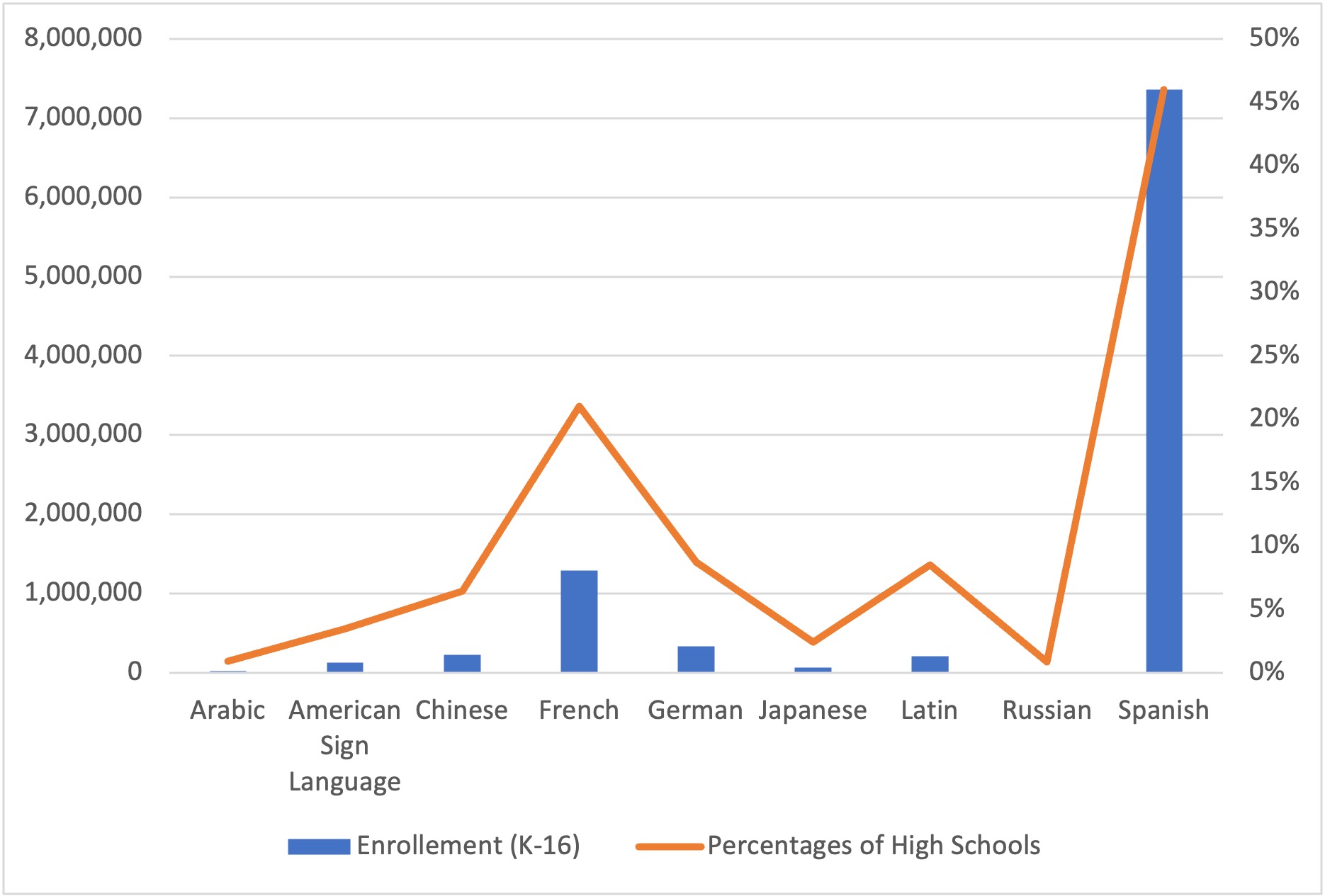

Graph 1: K-16 Language Learning in the U.S. 2014-5

Source: The National K-16 Foreign Language Enrollment Survey Report

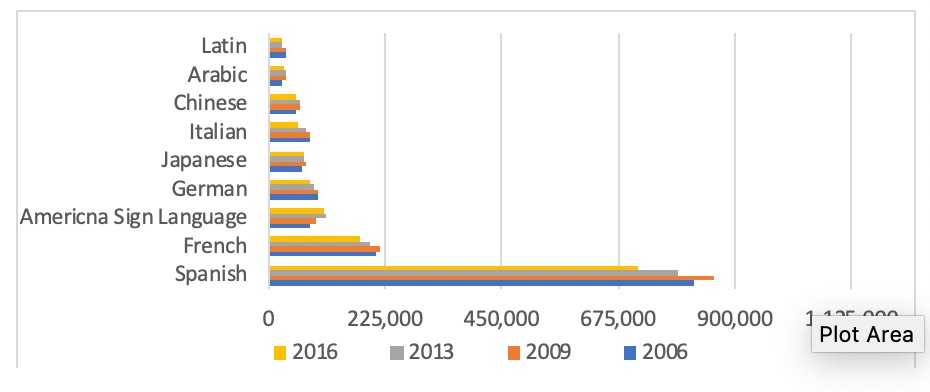

Language education is where preparation for a China-dominant world should begin and where it is most lacking. In 2015, Obama announced the launch of “1 Million Strong,” an initiative aimed at increasing U.S. learners of Chinese to one million by the year 2020. “If our countries are going to do more together around the world,” said Obama, “then speaking each other’s languages, truly understanding each other, is a good place to start.”9 Yet, Chinese language education has not seen the investment and interest that would allow for anything like this goal to be reached. The most recent comprehensive data from a 2017 National K-12 Foreign Language Enrollment Survey Report (Graph 1), shows that less than seven percent of high schools in the U.S. offered Chinese and that it came in as the fourth most-studied language, barely beating out Latin. In higher education the numbers are worse, with Chinese the seventh most-studied language (Graph 2).

Graph 2: Higher Education Enrollment in Modern Languages

Source: The National K-16 Foreign Language Enrollment Survey Report

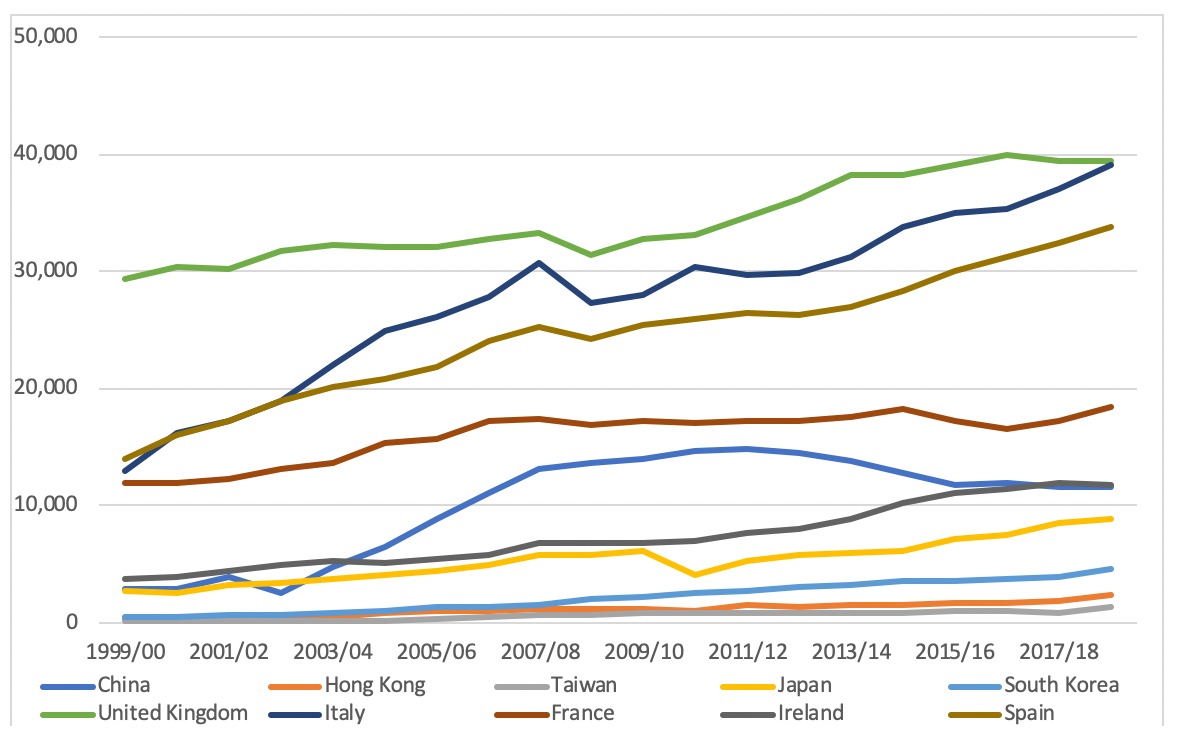

Nor are failures in Chinese language education limited to the United States. Two years after the first Mandarin immersion school attempted to open in Germany, difficulty with state regulation forced them to settle for Chinese three times a week, despite immersion schools already existing in French, English, Spanish, Italian, Turkish, and Russian. By contrast, China is learning English at a prodigious rate and hundreds of thousands of Chinese students flock to the U.S., UK, Canada, Australia, and other rich democracies for everything from high school diplomas to doctorates. While the number of U.S. students studying in China rose steeply in the early 2000s, in line with the Obama administration’s goals, the numbers then plateaued and began to decline in the mid 2010s. By 2019, more U.S. students studied in Ireland than in China (Graph 3).

Graph 3: U.S. Students Study Abroad Destinations 1999-2019

Source: Open Doors – Institute of International Education

Across a variety of departments, most universities do not have the expertise and faculty necessary to provide sufficient offerings related to China or Asia more generally. Beyond language, a trend away from area studies exacerbated a lack of expertise in China. One might expect political science, economics, business, history, and other departments to stock up on China experts as they did on Soviet specialists during the Cold War. But most seem satisfied with a single expert on East Asia (many of whom are actually Korea and/or Japan specialists). There appear to be fewer China-focused jobs in U.S. political science departments every year. In 2021, only a handful of U.S.-based China-focused jobs were advertised in political science, and these were primarily focused on security.

What makes this failure to invest in Chinese language education look even worse is the rejection of one of the few low-cost resources for education in Chinese, Confucius Institutes. CIs have been forced out of U.S. universities even though a bipartisan congressional commission determined that there is “no evidence that these [Confucius] institutes are a center for Chinese espionage efforts or any other illegal activity.”10 China spent more than $158 million on U.S. Confucius Institutes from 2006 to 2019, but after peaking at 103 in 2017, universities began to reject them and by the end of 2021, and only 31 remained. If China was really such a concern that the CIs had to go, then surely the lost investment in language training should be replaced, many times over, by funding from other sources.

Failing to build a robust Asia curriculum is inexcusable, even in tough budgetary times, because developing substantial infrastructure and profound expertise takes decades. From intelligence gathering to business, children well-versed in the languages and cultures of China and its neighbors are the best hope for rich democracies to compete with and relate to a rising China, but these are investments that will take decades to reap rewards. If rich democracies invest heavily in education programs related to Asia starting today, they will begin to see the results in a decade or two.

Yet, unlike the categories considered above, education seems to be an area in which rich democracies are not even slowing the pace at which they are falling behind. In part this is due to increasingly negative attitudes about China. While this may be understandable given increasingly negative rhetoric about China in the media as well as PRC policies such as the repression of Muslims, it seems to be self-defeating. If China is important enough to attract widespread suspicion, then it ought to be worth learning about. Students who hear ominous things about China could choose to study in Taiwan or Singapore or even Korea or Japan.

Conclusion

Considering the three areas – military, economics, and education – the U.S. and its rich democratic allies have largely, though not completely, failed to prepare for a world in which China is a, if not the, superpower. But preparations have been uneven and some of the areas demonstrate more foresight and investment than others. It is difficult to know whether the United States and its allies are prepared to deal with the rise of China militarily, but in line with generally substantial U.S. military spending and investment it seems clear that this is where preparations have been the most thorough, or perhaps the least neglected. Economically, both at home in the form of R&D support and abroad in terms of offering alternatives to China’s investment, there are clear signs of inadequate preparation and a shift in momentum. In the field of education, there are not even signs of concern as rich democracies fall further and further behind. In the next piece I will consider why, despite the relative predictability of China’s rise, rich democracies seem to have been caught so flat-footed.

The post Is the World Ready for China Risen? appeared first on China Research Center.

]]>The post China’s Nina Andreeva Moment appeared first on China Research Center.

]]>A similar episode occurred in China in 2021. A writer named Li Guangman, formerly editor of a trade publication for an electric power company and columnist for a website that no longer exists, posted a long commentary called “Everyone Can Sense that a Profound Transformation is Underway!” to his WeChat account in late August. Several media outlets immediately republished his essay, among them People’s Daily and Xinhua — two of the leading central-level news platforms in the country.

The tone and content of Li’s post echoed the militant rhetoric of the Cultural Revolution. After a lengthy diatribe against a few pop culture celebrities who had been canceled over tax evasion and offenses against traditional cultural values, Li noted other recent regime moves including the suspension of the IPO by Alibaba’s digital finance spin-off Ant Group, the new emphasis on the theme of “common prosperity,” and the grand celebrations of the Party’s centenary. All these actions, he claimed, signaled the coming of a “profound revolution” that would sweep away “capitalist cliques” and bring the “people” back to the forefront of society. In dramatic Maoist fashion, he celebrated “the return of red, the return to heroes, the return of blood” (hongse huigui, yingxiong huigui, xiexing huigui).” Like Mao and the Gang of Four, Li demanded thorough going cultural change. “We need to control all the cultural chaos and build a lively, healthy, masculine, strong, and people-oriented culture” (“women xuyao zhili yiqie wenhua luan xiang, jianshe xian huo, jiankang, yanggang, quianghan, yi renmin wei de wenhua”), Li said.[3]

Four days later, the editor of the aggressively pro-regime, anti-Western publication, Global Times, Hu Xijin, published a rebuttal of Li’s post.[4] Calling Li’s article misleading and inaccurate, Hu declared that China’s leaders had been following an orderly course of measures aimed at preserving the “reform and opening up” mixed economy model — which did not at all amount to a revolution. Hu particularly objected to the rhetorical tone, which he said “would evoke some historic memories and trigger chaos in minds and panic among people.”[5] Rather than publishing it in Global Times, however, he posted it to his personal blog. Then the censors ordered that the post was not to be shared on Weibo or WeChat. Several hours later, the ban was lifted, and the post could be shared again. Reports from media sources indicate that the regulators issued oral instructions to media editors acknowledging that Li’s post had a wider impact than they had anticipated. Rather than demanding that they rescind or refute it, however, they asked editors to balance it with less inflammatory content.[6] After that, the controversy subsided. Li Guangman continued to post content, but less heated. The leadership made it clear that they would continue to intensify restrictions against Western influences and press the common prosperity theme, but not shutter all large private businesses or enact draconian redistributive policies.

Like the Nina Andreeva affair, the Li Guangman episode revealed two things about the current state of Chinese policymaking. Most obvious is the ambiguity in policy about how much the state intends to balance market activity and private capital ownership with state control. Second, at a deeper level, that ambiguity indicates divergence in the positions of key players in the policymaking process over basic economic policy choices. There is a basic tension between Xi Jinping’s need for supreme leadership and the fact that the regime rests on a series of tacit understandings among powerful bureaucratic and business interests. A good indication of this is the incoherence intrinsic to the “common prosperity” slogan. There is a widespread expert consensus around concern over high inequality and the need to build a middle-class society, one where the middle-income strata are the dominant force in society. One recent commentary notes that China’s society is about 30 percent middle class and argues that China can improve economic and social stability by raising that proportion to two-thirds.[7] However, the leadership has consistently avoided acknowledging the extreme concentration of income at the upper end. Instead, it has consistently asserted the need to raise low-end incomes through measures such as a higher minimum wage and more effective social assistance programs. Despite the conspicuous assaults on a few visible tycoons and celebrities, even in the most recent phase, the leaders have been cautious about arguing for an effective progressive income tax system, an estate tax, or surtaxes on high incomes. The regime is moving extremely cautiously in introducing a property tax, for instance, authorizing only small-scale local experiments.

An example of current mainstream thinking on the issue of inequality is an essay co-authored by the prominent economist and expert on inequality, Li Shi, dean of the Institute on Sharing and Development (gong xiang yu fazhan), at Zhejiang University and an associate at the institute, Yang Yixin.[8] The essay discusses Zhejiang Province’s pilot program to build “common prosperity.” While using the standard image of an “olive-shaped society” — the model of a social structure that is thickest in the middle and thinner at the two ends — the essay is anything but radical. It does propose taxes on wealth, such as estates and real estate, but only in the course of time. The authors do not argue for a progressive income tax. They call for “high-quality development” that expands incomes in the middle, but their only concrete prescriptions promise more “digitalization” and the “sharing economy.” They want to build middle class wealth by making sophisticated new financial products more widely available, assuming that more financial sophistication would spur economic growth. They want to reduce the incomes at the top by encouraging more charitable donations (i.e. “tertiary distribution”) but do not propose using the tax code to create incentives for that purpose. They call for extending social rights to migrant workers, but only gradually, and without hukoureform. They call for the use of “collective consultation” (xie shang) rather than collective bargaining between organized labor and employers over wages.[9] Most of the calls for improved workers’ wages, in fact, have to do with incentive pay rather than base pay. Are these as far as the writers can go? Or are these progressive-minded economists so fearful of the Maoists that they think they must guard against any serious shifts in social or fiscal policy? Substantively, the essay reveals policy experts’ reluctance to discuss the many forms of rent extraction that a state-dominated, cronyistic economy permits, the ways in which income rents support the Party’s political monopoly, and the forms of privilege that prevent real mobility of capital or labor across sectors and regions. They bind the regime’s political elites with businesspeople, state and private, who generate the rents the Party uses to maintain its power. Little wonder that serious reform-minded economists stop well short of analyzing the political economy of the regime.

At present, policymakers are working to deflect the “common prosperity” initiative into politically policy concepts.[10] A visible example is the idea of “tertiary distribution.”[11] In Chinese parlance, primary distribution is the result of the marketplace, where contributions to production determine the returns to labor and capital. Secondary distribution occurs through redistributive mechanisms, specifically taxes, social insurance contributions and benefits, and social transfers. Tertiary distribution — the channel that the current policy emphasizes as the way to achieve “common prosperity” — is voluntary donations of money and time to the nonprofit sector. Experts are calling for a reform of the tax code to provide material incentives through tax deductions for such contributions. However, given the current political climate, many wealthy individuals have found it expedient to make sizable and well-publicized donations to worthy causes. Lacking in the current debate is a reconsideration of more basic economic and political institutions that have fostered cronyistic and corrupt exchanges of benefits between wealthy entrepreneurs and political officials.

Therefore, when we interpret Xi’s gestures against Westernized entertainment industry stars, the private tutoring industry, and —selectively — against big digital platform companies as a broad “crackdown on everything,”[12] we overlook the fact that this is a highly selective and politically motivated campaign. Because regionalism, cronyism, and corruption are so deeply interconnected, enabling tycoons to amass wealth and power by cultivating mutually beneficial ties with local officials, it makes political sense for Xi to single out Jack Ma’s Zhijiang-based business empire and the regional officials who were closely tied to him: the campaign strikes at all three problems at the same time.[13]

The calls for “common prosperity” therefore reveal the limits on policy choices available to Xi. These are grounded in the multiple compromises his regime must make to retain power, between the monopoly of an ideologically driven communist party and its dependence on an economy dominated by politically favored state and private companies that feed the regime with taxes, kickbacks and privileged ownership shares. The leaders seek to respond to rising awareness of the extreme economic inequality in the country by taking measures to curb the excesses associated with particular firms and sectors, and by reaffirming Communist values. At the same time, they dare not move too far toward policies that would seriously harm the interests of the richest strata of entrepreneurs and managers who have locked in their advantageous positions by cultivating the favor of politicians at the local and national levels. Little wonder that new leftists are seizing on the opportunity to press for a radical turn away from the partial reform economy back toward Maoism, or that establishment party leaders and experts find it necessary to warn against any substantial steps toward a more far-reaching redistribution of wealth. In a polity where ideology and power are intertwined, the deepening of contradictions between the avowed doctrines of the regime and the actual institutions and practices its power rests on results in a gulf no amount of central control can bridge.

[1] Nina Andreeva, “Ne mogu postupit’sia princtsipami,” [I cannot violate my principles] [https://diletant.media/articles/34848945/]

[2] Thomas F. Remington, “A Socialist Pluralism of Opinions: Glasnost and Policy-Making under Gorbachev”, The Russian Review 48: 3 (1989), pp. 271-304.

[3] [http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2021-08/29/c_1127807097.htm] The reference to masculine cultural imagery alludes to the frequent complaint that the prominence of androgynous styles of self-presentation (sometimes called “sissy-boy” styles [jingzhunan or simply jingnan, ie refined pig boys or refined boys] on the part of some male entertainment industry figures. This fad became the target of heated cultural criticism in recent years for its violation of traditional gender role stereotypes. Under the current crackdown, commercial ads and television programs may not use such images.

[4] https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3147548/viral-blogger-hailed-chinas-profound-revolution-state-may; https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinese-essayist-revives-worries-about-a-new-cultural-revolution-11630670154;

[5] https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3147548/viral-blogger-hailed-chinas-profound-revolution-state-may; https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinese-essayist-revives-worries-about-a-new-cultural-revolution-11630670154.

[6] https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3147548/viral-blogger-hailed-chinas-profound-revolution-state-may.

[7] Zhang Jun, “Gong fu hui xiaochu shouru chabie, dan ke baozhang diceng timian shenghuo,” [https://fddi.fudan.edu.cn/15/20/c18965a398624/page.htm#:~:text=8%E6%9C%8817%E6%97%A5%E5%8F%AC%E5%BC%80,%E7%9A%84%E6%A9%84%E6%A6%84%E5%9E%8B%E5%88%86%E9%85%8D%E7%BB%93%E6%9E%84%E3%80%82&text=%E5%85%B1%E5%90%8C%E5%AF%8C%E8%A3%95%E6%98%AF%E5%90%A6%E5%B0%B1%E6%98%AF%E6%B6%88%E9%99%A4%E6%94%B6%E5%85%A5%E5%B7%AE%E5%88%AB%EF%BC%9F]

[8] Li Shi and Yang Yixin, “Jianshe shouru fenpei zhidu gaige shiyan qu zhu tui gongtong fuyu” [“Establish reform of the income distribution system by a pilot zone for common prosperity”][http://www.ce.cn/xwzx/gnsz/gdxw/202108/19/t20210819_36821588.shtml] August 19, 2021

[9] On this distinction, see Thomas F. Remington and Cui Xiaowen, “The Impact of the 2008 Labor Contract Law on Labor Disputes in China,” Journal of East Asian Studies 15:2 (2015), p. 280.

[10] For example, see the spate of articles in Caixin Global explaining that “common prosperity” does not mean “robbing the rich to give to the poor” and that it is an encouragement to more “tertiary distribution.” For example, Cai Xuejiao, “’Robbing the Rich’ Is Not Part of China’s Plan for ‘Common Prosperity,’ Official Says,” Caixin Global, August 26, 2021; Wang Tao, “What Does ‘Common Prosperity’ Mean for China’s Policies and Economy?” Caixin Global, August 27, 2021.

[11] Eg. Kevin Guo, “CX Daily: What’s Standing in the Way of ‘Common Prosperity’?” Caixin Global, September 10, 2021 [https://www.caixinglobal.com/2021-09-10/cx-daily-whats-standing-in-the-way-of-common-prosperity-101771292.html]; Caixin Global, “Editorial: Releasing the Potential of Tertiary Distribution,” Caixin Global, August 23, 2021 [https://advance-lexis-com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/document/?pdmfid=1516831&crid=3b2d80b9-253e-4bf0-a656-90ef416dd531&pddocfullpath=%2Fshared%2Fdocument%2Fnews%2Furn%3AcontentItem%3A63F7-M2R1-DY28-G00P-00000-00&pdcontentcomponentid=468180&pdteaserkey=sr9&pditab=allpods&ecomp=nzvnk&earg=sr9&prid=3c59210a-fdc4-4d3a-95cb-a8fd4011aafc]

[12] Lily Kuo, “Xi Jinping’s Crackdown on Everything Is Remaking Chinese Society,” Washington Post, September 10, 2021.

[13] Lizzi C. Lee, “Xi Jinping’s Graft Busters Are Probing Jack Ma’s Home City, and a Rising Star of Xi’s Zhejiang Clan,” SupChina, August 31, 2021 [https://supchina.com/2021/08/31/xi-jinpings-graft-busters-are-probing-jack-mas-home-city-and-a-rising-star-of-xis-zhejiang-clan/]

The post China’s Nina Andreeva Moment appeared first on China Research Center.

]]>The post Book Review: Red Roulette by Desmond Shum appeared first on China Research Center.

]]>Book Review: Desmond Shum, Red Roulette (Scribner, 2021); 310 pp. hardback

Billed as a “tell-all” about the scandals of the Chinese Communist Party as it led China’s re-entry into the global system, this tale is a page-turner of policy shifts and intrigue, including the mysterious disappearance of the author’s wife. Shum’s main takeaway is that the CCP only cares about its power and protecting the top cadres’ children, who will carry on and protect the current leaders in their retirement. At the core of what Shum calls the “red aristocracy” are the original cadres who fought along with Mao Zedong, and the “princelings,” their offspring. China’s economic success, Shum argues, was achieved by connecting entrepreneurs to these political elites, an arrangement that served the interests of both. In Shum’s view, that arrangement has run its course, as President Xi, one of the princelings, pushes Chinese socialist values while condemning western ones.

Shum was born in Shanghai in 1968 but moved with his family to Hong Kong, which was not easy to arrange, especially because Shum’s father did not come from a “good” background — people who supported the CCP once they won the civil war in 1949. Shum’s grandfather had been a lawyer in Shanghai, which made him a capitalist and therefore a bad element. His father ended up in a low position teaching Chinese at a Shanghai teachers’ training school and met his mother there. But his mother had relatives in Hong Kong who helped her get to the British colony. But it took years of cajoling authorities to let his father join her in Hong Kong.

Ironically, once China began to reform, Shum’s mother and father willingly moved back to Shanghai to make fortunes. Shum’s father had a successful stint with TysonFoods in Hong Kong, and the company sent him to Shanghai to build its China market. Shum moved back to China as his company’s representative in Beijing in 1997. He lived as an expat gaining business experience but without much success.

Shum’ business career took off when he met Whitney Duan (Duan Zong) in 2001. They became business partners, eventually married and later had a son. The book opens with the fact that Whitney disappeared in 2017, and that Shum had not heard from her or received any news about her since.

Whitney, who was born in Shandong Province in 1966, started a company called Great Ocean. As a Christian, she vowed never to get ahead by being corrupt. However, she was adept at cultivating relationships with people at the highest levels of the Chinese leadership. She became especially close to Auntie Zhang (Zhang Beili), who was the wife of Wen Jiabao. Wen rose in the political ranks to become Premier from 2003 to 2012.

Through their tirelessly cultivated connections, Shum and Whitney were able to obtain valuable pieces of land and permission to build major projects, including the cargo area of the Beijing Airport and a large office-condo complex nearby. Through their development company and access to other sure-bet investments, they were able to make hundreds of millions of dollars over the years.

Three aspects of Shum’s story are especially intriguing.

First, he provides a clear description of how connections, guanxi, work and offer rewards in China. In the Chinese context, guanxi — like networking in the West — does not mean corruption, but Shum argues that to do any business in China one must curry favor with the Communist Party.

Second, one can see how business changed as reforms advanced and the business environment evolved due to new regulations, infrastructure buildout, rising incomes, and interaction with global markets.

Third, Shum’s description of the changing environment matches nicely with a recent article explaining the man behind the big ideas of the top leadership in the CCP: Wang Huning (https://palladiummag.com/2021/10/11/the-triumph-and-terror-of-wang-huning/).

Shum describes the capitalist experiment as alive and well in the early 2000s, but he saw the backlash against liberalism picking up steam in the mid-2000s. In the early 2000s, state-owned enterprises were being listed on the New York Stock Exchange, private companies had some access to bank loans, the housing market had taken off, and the middle class was growing and spending. People like Wang Qishan, a reformer, had risen to power. Wang was vice premier in 2008 under Wen Jiabaon and a close friend of Whitney’s.

By 2006, however, there were signs that capitalism was not going to work in China after all, which only accelerated with the global financial crisis in 2008. Changes that followed made it harder to do business, such as requiring private and joint venture firms to have Party committees, and regulations that gave state enterprises advantages over private firms. About that time civil society also began to feel increasing pressure to conform to Party demands.

Overall, Shum argues that despite the seemingly capitalist “experiment,” the leaders never intended to end the Communist system. For example, listing state enterprises on stock exchanges was not a move to privatize them, but rather a way to strengthen these companies to compete globally with the private sector. The shift to reassert Party control over the economy and society had begun. The Party leadership ladder changed too — less moving up the local ranks (as these people were difficult to manage) and instead bringing in loyalists from other regions.

Shum suggests that he and his business friends did not want to overthrow the Party. They did want a more open system. He and others willingly donated some of their vast wealth to support education and other social improvements. But Shum increasingly saw private companies and entrepreneurs being used by the Party, and that long-term, private investment was not a realistic option. Get in, make money, and sell out as fast as you can — that became the goal.

China’s successful economic growth and the improvement of the state sector meant the Party did not need the private sector as it did before. Hence it was no longer essential to have lax Party control over business. Shum argues that repression and control are the foundations of the Party, and this has not changed with the modernization of China under reforms. In 2012, Document No. 9 titled “Briefing on the Current Situation in the Ideological Realm” appeared. It warned of dangerous western values such as free speech. The situation has continued to worsen since then.

Just before the publication of Red Roulette, Shum received a call from Whitney. As described in a segment of Australian 60 Minutes on September 26, 2021 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bOtVMFPjNUA), she had been at least temporarily released from detention, where she had been cut off from all news of her family, China, and the world. She asked Shum not to publish the book and said if he did, he and their son would be in serious danger. She called a second time as well, but Shum chose to tell their story to help the world understand the challenges of the business environment in China and the political realities behind it. Not everyone deals with such extremes of corruption and power in China as described by Shum, especially if they are located outside of Beijing. But this story helps put into perspective some of the current policies in China today, such as the anti-corruption campaign and President Xi’s move toward reestablishing socialism as the Party’s most salient goal. The bottom line is that the Party, led by President Xi, is trying to ensure that it stays in power for the long haul.

The post Book Review: Red Roulette by Desmond Shum appeared first on China Research Center.

]]>The post Hongqi: from Mao to Xi appeared first on China Research Center.

]]>Xu was born and raised in the FAW. His father, Xu Zuoren, was a founding member and deputy director of the company. Xu Jianyi was born in 1953, the same year that FAW was founded. His father named him Jian (build) Yi (first) after the First Automotive Works. As a “second-generation FAW,” he got promoted quickly through the ranks after starting to work at the company in 1975. Xu spent at FAW for 36 years, his entire working life except for four years when he worked as a mayor in local government. From 2010 to 2015, he was the president and party secretary of the FAW Group. Instead of receiving compliments on Hongqi’s success in the new era, the man who was born to rule FAW was placed under Party detention and investigation in March 2015. He must have wondered where it all went wrong.

The story of Xu Jianji and the automobile maker he helped build is more than an epic tale of rise and fall and personal sacrifice. It is a window into how state-owned enterprises have evolved through the historic upheavals that have marked China from the founding of the People’s Republic until now. This essay then offers a brief introduction to the history of Hongqi from Mao to Xi.

Former chief Hongqi designer Chen Zheng also was swept away by stormy political winds. Inspired by fashionable Italian cars, Chen made the 1962 Hongqi CA72 model slimmer, flatter, and sportier by virtue of exterior design changes. The new look, however, only brought him misfortune. His father, Cheng Ke, had been mayor of Tianjin before 1949. Cheng Zheng was a car enthusiast and an artist who bought a secondhand motorbike and rode around the countryside, finding inspiration. But his family background helped earn him a conviction for designing a “flat belly car” that was “a vicious attack and mockery of the Great Leap Forward movement and the great famine.” He was also criminalized for being a “hypocritical person living the Western lifestyle.” He and his sample car were paraded through the FAW and subject to public criticism. His wife very publicly divorced him because of the political pressure, and he was sent to the assembly line as a cleaner.

Consecration: Hongqi and FAW from 1956 to 1984

The First Automobile Works was the first major state-owned automotive manufacturing company in China. Its purpose was to manufacture military and industrial trucks. In July 1956, the first Jiefang (Liberation) truck rolled off the assembly lines. Chairman Mao was pleased after the presentation of the truck in Beijing and said, “It would be great if one day we could ride in our Chinese manufactured saloon car to attend meetings.” It was the beginning of the consecration of FAW and the Hongqi model.

In 1957, the Chinese central government ordered FAW to manufacture a saloon model for the national leaders. After collecting information on the most advanced modern luxury saloon cars available in the 1950s, FAW chose to reverse engineer the Simca Vedette and the Mercedes-Benz model 190. The result was China’s first indigenous saloon car; the Dongfeng CA71 manufactured in 1958. The model was named Dongfeng (East Wind) based on the quote from Mao’s speech in Moscow: “The east wind prevails over the west wind.” Initially, the Dongfeng’s nameplate used the Roman alphabet, but Beijing urged FAW to change it to Chinese characters handwritten by Mao and add a company logo to the side of the car written by Mao. In 1958, FAW top managers Rao Bin, Shi Ruji, and Li Lanqing took the Dongfeng CA71 to Beijing to present it outside Huairen Hall, Mao’s residence. All national leaders were summoned to view the car.

During the presentation, Premier Zhou Enlai opened the hood and asked, “I heard this engine is copied from Mercedes-Benz model 190, right?” Shi Ruji answered, “Yes.” Zhou said, “All major automotive brands copy from each other. But we need to do it cleverly, and we have to make some changes; if we copy the engine exactly, they would be unhappy. For example, we can change the shape of the valve chamber cover.”

This was the moment of consecration of FAW and service to Mao directly. The marriage made FAW – and later the Hongqi model – sacred, a political symbol of the state-owned economy. FAW managers, engineers, and workers were not only manufacturing cars, but they are the direct servants of Mao. These were not mere cosmetic honors but actual political assets that had brought personal advancements and tragedies to FAW managers and engineers.

From 1953 to 1956, FAW sent around 500 engineers to the Soviet Union. Many of these engineers were promoted to important positions later on. Two eventually became top party leaders. Li Lanqing served as Vice Premier of China from 1998 to 2003. Jiang Zemin became the Party General Secretary and the President of China from 1989 to 2003. During Jiang’s 15-year presidency, he paid official visits to FAW three times. He often called himself “an FAW man.” He took countless official photos in the same spot beside Chairman Mao’s handwritten inscription stone of FAW.

Only 30 Dongfeng CA71 model cars were ever manufactured. As a vehicle for Mao himself, the model used the best possible material, such as silk brocade seats, velvet ceilings, wool carpeting, lacquer-wood control panels, carved ivory switches, and cloisonné smoking utensils. However, it was not a reliable car. It broke down frequently. The reverse engineering methods used to make it were crude, reflecting China’s lack of technological and manufacturing knowledge. But the Dongfeng laid the foundation for the development of the Hongqi model. At the height of the Great Leap Forward movement in 1958, FAW announced a plan to build a more luxurious saloon car 90 days after the first Dongfeng CA71 model was manufactured. The idea was to produce a completely new model with better performance and reliability within a month. FAW engineers based the design of Hongqi model on a 1955 Chrysler Imperial bought from the Yugoslav Embassy in China and borrowed from the Jilin Institute of Technology. The most challenging part of making the Hongqi model was reverse-engineering the V8 engine.

Soviet experts had told FAW engineers to give up on the V8 engine design because even the USSR could not produce an eight-cylinder engine in 1958. This inspired FAW managers and engineers, and they set out to prove they could do what the mighty Soviet Union could not. The plan: hand-cast 100 engine blanks based on the Chrysler engine, choose the three best ones and assign each to a team of engineers and craft workers, who labored day and night for two weeks to hammer out a prototype. The best one was picked to put in the experimental CA72-1E model. In August 1958, after 33 days of intense work, the first Hongqi model was manufactured. It was named Hongqi (Red Banner), meaning the car was designed and built “holding the great red banner of Chairman Mao’s Thoughts up high.” Within two months, FAW produced a convertible version of the CA72 model for the 10th national day military parade. These were abnormal model development time frames with unusual methods of production. It was a lavish sacrifice to support Mao’s Great Leap Forward movement.

Engineers at FAW had spent a year testing and upgrading the design of the CA72 based on two other advanced saloon models, the Cadillac Fleetwood and Lincoln Continental. The finalized version was manufactured in August 1959. The design of the CA72 model was classic with strong Chinese elements. The design was a mixture of imperial residuals and Communist political symbols, such as the fan-shaped grille and the Chinese royal lantern-shaped taillight. There were five little red flags representing worker, farmer, merchant, student, and solider on the side of the car. In 1960, FAW designed a three-row CA72 model that carried three little red flags representing the General Path, Great Leap Forward, and People’s Commune, representing Chairman Mao’s three key political philosophies in 1960.

In September 1964, the Hongqi model was declared China’s “National Car.” It became the official vehicle for national events, diplomatic missions, and national leaders. However, the Cultural Revolution severely curtailed the production of Model CA72. Only 206 units were ever produced. In 1965, a new Hongqi CA770 model was designed by Jia Yanliang, who was just 25 years old. It contained a redesigned exterior and engine. The new engine was based on Cadillac V8 engines with two-speed automatic transmissions. Party leaders directly participated in the design of the car to add more luxury features. In 1966, the first 52 units of the Hongqi CA770 model were transported to Beijing and distributed to national leaders with interior colors of their choosing. In 1969, the first Hongqi CA772 bulletproof model was manufactured. The development team was led by Mao Weizhong, from the Central Security Guard Bureau of national leaders. Other team members included military experts in bulletproof armor. The model contained 6mm bulletproof armor, 65mm bulletproof windows, and tires that could run 100 miles after bullet penetration. The car weighed 4.92 tons and was regarded as the safest car in the world in its time. The Hongqi CA772 model earned an infamous part in Chinese history as Chairman Mao’s appointed successor, General Lin Biao, fled in it to the airport in 1971. Bullets fired by guards only scratched the surface of the armor.

It was the height of glory for Hongqi. However, just like CA72 and its designer Cheng Zheng, the sacred status of Hongqi also brought tragedies to its designers. The initial design had three red flags on the side of the CA770 model representing “Mao’s General Line, Great Leap Forward and People’s Commune.” Beijing Mayor Peng Zhen suggested that FAW change it to one big flag representing “Mao Zedong Thought.” During the Cultural Revolution, the single-flag design became the basis for one of Peng Zhen’s criminal charges and evidence that he had attacked “Great Leap Forward and People’s Commune.” Hu Yuyong, the general manager of FAW, and Jia Yanliang himself were publicly criticized for cooperating with the criminal Peng Zhen. Jia was expelled from the position of chief designer of Hongqi until 1972.

The development of Hongqi CA773 model started in 1968. However, the FAW saloon car development team was abolished during the Cultural Revolution, and all engineers were sent to work in the factory as assembly workers. Workers on the assembly line took over the job to develop the Hongqi CA773 model. These barefoot doctors of the factory floor demonstrated the foolishness of favoring “red” over “expert.” The Hongqi CA773 model was in production from 1969 to 1976, but due to various design faults and quality issues, only 291 units were produced in seven years.

Hongqi development resumed in 1972. FAW engineers began designing the CA774 model. The development team was led by Jia Yanliang, the designer of the CA770. The idea was to catch up and overtake the most advanced saloon car in the world. To achieve that, Jia designed four sample models in 1975 with bold changes from previous Hongqi models. The new design was advanced and modern and included the use of arc-shaped side windows to improve aerodynamics. The car body was made of high-strength steel sheets to reduce weight. It was the first time a Chinese automaker had used a modern monocoque body frame design. However, the design conflicted with some functions of the car. The aerodynamic shape was regarded by some officials as lacking in solemn status compared to the old square shape. There were safety concerns about the big, transparent car windows that overexposed passengers and officials rejected the most modern, bold Hongqi CA774 model. The attempt to upgrade the Hongqi failed. Its symbolic and sacred status as Mao’s car prevented its modernization. In 1976, FAW made an unsuccessful attempt to upgrade the Hongqi model by seeking joint development with Porsche. In 1976, Chairman Mao died. The central government ordered FAW to create a vehicle for the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall to carry the Chairman’s corpse in case of an emergency. It was the last Hongqi made for Mao.

The Weakened Hongqi in the 1980s

In 1979, FAW resumed the development of the CA774, with Cheng Zheng came back as the chief designer. After the Cultural Revolution, his design turned conservative, back to a non-bearing body system with reduced window size to comply with the government’s safety requirements. But the central government had lost interest in new Hongqi models, and Cheng’s design was never manufactured. As a highly politicalized symbol that was closely associated with Mao, the sacred status of Hongqi faded temporarily with Mao’s death.

With economic reforms undertaken by Deng Xiaoping, the technology gap between state-owned auto manufacturers and the international automotive industry became apparent. Top Party officials started to complain about the Hongqi. FAW was experiencing huge financial losses. The vehicle had high fuel consumption and poor reliability. There were moments of diplomatic embarrassment when cars broke down after picking up foreign leaders from the airport. The last straw was a serious accident caused by brake failure when the Romanian president was visiting the Great Wall. There were political reasons for Hongqi to fall out of favor, too. Modernization, the market economy, and westernization were the new trends in China. Hongqi was regarded as a symbol of conservative, bureaucratic debris that needed to be reformed. At the time, economic reform was the priority, and after Mao’s death, the glory surrounding the man was deflated.

In 1981, FAW President Rao Bin and the General Manager Li Gang were summoned to Beijing and told of the decision to cease Hongqi production. Rao argued with Premier Zhao Ziyang over the decision in the meeting, saying, “Four people carrying a palanquin is different from 12 people carrying a palanquin. (Palanquins were enclosed sedan chairs in which officials were transported by men holding long poles.) The car is bigger and heavier, so fuel consumption is higher. Fuel consumption of the Hongqi is not much higher and foreign luxury models. The unit production cost is ten times more than a Jiefang truck. The factory is suffering a loss on the Hongqi, but it is for our national leaders, and it is a way for FAW to express our patriotic hearts.” Zhao rudely interrupted him and said, “你别打肿脸充胖子了” (“Don’t slap your face until it’s swollen in an effort to look imposing.”). The harsh Chinese proverb means someone is bragging. Rao then asked, “What about the future of our indigenous saloon cars for leaders?” The one-word reply he received was “importation.” In May 1981, the People’s Daily announced the order to cease production of the Hongqi. It was perceived as a strong signal of economic reform. National leaders started to ride in imported cars. In 1984, China had imported a large number of Toyota Crown models from Japan as official vehicles and Mercedes S-Class for national leaders.

Once Party leaders, the only customers of the Hongqi, decided to abandon it, FAW had only two choices: let the Hongqi disappear or face the mass market. FAW chose the latter. But that required cooperation with major carmakers from around the world. Two years after ceasing production of the Hongqi, the first major automotive international joint venture, Beijing Jeep, was established between American Motors Corporation (AMC) and Beijing Automobile Works (BAW) in Beijing. The Chinese automotive industry had entered a new era.

The Rebuilding of FAW from 1985 to 1995

A strategy of 市场换技术 – “give market access in exchange for technology” – policy emerged in the 1980s. It was proposed by Rao Bin, who was promoted to be Chairman of the China Automotive Company in 1982. He had a clear vision about the future of the Chinese automotive industry: change the Soviet industry structure and shift resources from heavy industrial/military vehicles to civil passenger cars. Rao wanted the automotive industry to become a pillar of the Chinese economy. As the founder of FAW and SAW, he recognized the technology gap, and encouraged state-owned enterprises to import technology and set up joint ventures with advanced carmakers. He was involved in all the major joint venture negotiations in the 1980s, including the deals for SAIC-VW to manufacture the VW Santana model, Beijing-Jeep-Chrysler to manufacture the Jeep model, and Nanjing Automotive Corporation Group-FIAT to manufacture NAVECO.

Although there was no Hongqi model in production from 1981 to 1996, the development of the Hongqi model never ceased in FAW. Building on the experience of a failed negotiation with Porsche, FAW’s strategy was to develop the model with foreign manufacturers jointly. The goal was to bring advanced foreign technologies to FAW as a foundation to build indigenous models. Lu Fuyuan was the chief negotiator for FAW. In 1982, the company started to hold talks with international carmakers, including Nissan, Ford, Chrysler, and Audi.

Meanwhile, FAW engineers were researching the most popular sedan models of these brands as foundations to build the new Hongqi model. However, the results were counterintuitive and chaotic, as FAW reimagined the Hongqi using reverse engineering methods of the past. In 1982, the model CA750 was patterned on the Nissan 280C, using engines, gearbox, and chassis from the 280C model. In 1984, FAW engineers had installed a Ford 5.8L V8 engine in the CA770 model and redesigned the interior based on Lincoln models. In 1986, FAW engineers developed a new Hongqi model based on the Dodge 600 with Chrysler 488 engines. These three models never went into production because FAW could not reach an agreement with the car companies. Chrysler promised to sell its Dodge 600 production line to FAW in 1987 after FAW bought the Chrysler 488 engine production line. However, the American company increased the price of the Dodge production line, and FAW did not pursue the purchase. FAW was left with a Chrysler engine production line without a means to manufacture a car with it. With no international partners, some engineers in the FAW resumed the effort of redesign the Hongqi model independently. However, their efforts never resulted in production either. These chaotic efforts to build a new Hongqi model reflect the state of FAW of the time. It had lost its totem and was desperately trying to adapt to the new structure of the “profit and efficiency first” world.

FAW managers learned that it was challenging to purchase technologies from international car companies without further collaboration. In 1988, FAW established the FAW-VW with Audi and VW to produce the Audi 100 model through the help of an old comrade of FAW. Jiang Zemin worked at FAW from 1954 to 1962 in the power chain department as an engineer. Shen Yongyan, a close friend and colleague of Jiang, became the Deputy Chairman of FAW in the 1980s.

In 1986, FAW was facing financial difficulties. Geng Shaojie, the president of the company at the time, was discreetly preparing to produce saloon cars. FAW had negotiated with American and German carmakers and was ready for collaboration. Around that time, another Chinese state-owned automaker, SAIC in Shanghai, was working with the VW group to produce the VW Santana. In the summer of 1986, SAIC started to assemble an Audi model using SKD (knock-down kit) technology on the Santana production line. Geng Shaojie heard about this news and urgently ordered Shen Yongyan to go to Shanghai and meet with the then Mayor Jiang Zemin. They planned to negotiate with SAIC to help them meet the target of 65 percent domestic production rate of Santana parts in exchange for SAIC giving up on the production of the Audi model and letting FAW collaborate with Audi. They had the meeting at Jiang’s residence at night. The deputy mayor in charge of the Shanghai automotive industry was summoned by Jiang. Shen explained to Jiang that producing Santanas and Audis were two very different tasks. The factory needed new mold equipment. SAIC could assemble a few units using SKD, but it did not have the capacity to mass-produce Audis. In Germany, Santana and Audi were produced in two factories. FAW had a strong foundation with its rich experience of producing top-class saloon cars, even if the Hongqi production line was closed. If SAIC could leave the Audi production to FAW, FAW could help to manufacture Santana components domestically. This would be beneficial to SAIC and FAW. FAW could get the central government’s support to resume high-class saloon car production in China. Shen was trying to persuade Jiang and to test SAIC’s reaction. Jiang thought for a while and looked around the room and said, “That’s fine.” One year after the meeting, the central government announced FAW and Dongfeng would be the two major manufacturers of saloon cars, the critical task of SAIC was to localize the production of Santana parts. The central government would not approve any new saloon car manufacturers in China.

By the end of 1988, VW informed FAW about the availability of the Westmoreland plant south of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The plant went into operation in April 1978 with an annual production capacity of 300,000 units of VW Golf models. The main plant covered 260,000 square meters and had three production lines, including body welding, painting, and assembly. These production lines and machinery represented advanced technology to FAW. Meanwhile, another Chinese state-owned car factory, SAW Dongfeng, had entered negotiations with other car companies on advanced saloon model production. FAW was in desperate need of securing these production lines from VW. To disguise its desperation, FAW chief negotiator Lu Fuyuan picked just one colleague, Li Guangrong, the deputy chief engineer of foreign relations, to form a modest two-man negotiation team to go to Germany.

Lu Fuyuan was born in a rural farming family. He self-studied English, Japanese, and Russian, as well as radio transmitter technology and computer science as a FAW worker. In his spare time, he translated instruction handbooks for imported machinery. With his excellent language skills and technological knowledge, he discovered faults in some imported machines that failed to perform to the standard in instruction handbooks. He was promoted by the FAW leadership to take charge of negotiations with suppliers and seek compensation. He was later sent by FAW to study computer programming design in Canada. In 1985, Lu was promoted to vice manager of FAW. He was put in charge of managing foreign partnerships, joint venture negotiations, and technology importation. He was constantly traveling between China, Europe, and America, and was called the “Kissinger of FAW,” and represented FAW in all major negotiations with international car companies in the 1980s. His diplomatic skills and persistent qualities were on display in lengthy negotiations, earning him a promotion to the deputy minister of the Ministry of Machine-Building Industry and later to Minister of Commerce in the 1990s.